In October 312 AD, Constantine stood before the Milvian Bridge and gazed into the noonday sun. He claimed to see a fiery cross superimposed upon it, bearing the words, “In hoc signo vinces” —“By this sign, conquer.” That night, he was said to have received a dream instructing him to mark his soldiers’ shields with the Chi-Rho, the emblem of Christ, and march on Rome (Odahl, 2010). He did so, transforming a minority faith’s symbol into an imperial standard and securing victory. Later coinage even depicted an angel placing a crown on his head as he clutched that same standard, proclaiming divine legitimacy for his rule.

This moment marked more than a military triumph; it signaled a radical reimagining of sovereignty. Jesus, once supposedly thought of as a Galilean preacher who refused earthly crowns, but more recently classed as a demigod within the Greco-Roman religious world, had now entered the command structure of the Roman army, and not just metaphorically, but structurally. In doing so, Constantine followed a pattern deeply embedded in the ancient world: the transformation of supposedly divine figures into cosmic sovereigns whose will shaped the laws of empire.

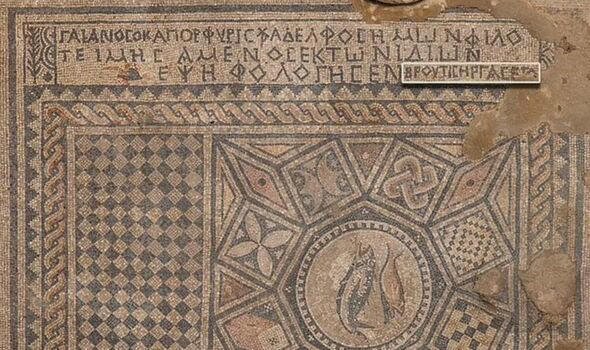

This phenomenon finds a striking parallel in the earlier reign of Ptolemy I Soter, ruler of Hellenistic Egypt. Ptolemy sought to unify Greek and Egyptian populations under a single imperial cult, introducing Serapis (a syncretic deity merging Greek and Egyptian traditions) as the divine patron of the Ptolemaic state (Pfeiffer, 2008). Serapis was not merely a god of healing or the underworld; he became the celestial counterpart to the ruling royal pair, Isis being his mythological consort. By aligning the king with this newly crafted divine figure, Ptolemy ensured that the monarchy could be worshipped as a living embodiment of cosmic order—a model later echoed by Constantine.

Like Constantine, Ptolemy understood that the fusion of religion and statecraft was not simply a matter of political convenience; it was a philosophical necessity. Just as Constantine saw in Christianity a unifying force capable of binding together a fractured empire, Ptolemy saw in Serapis a symbolic bridge between cultures. Both leaders recognized that gods must become kings, and kings must become gods, if they were to hold together the vast, diverse populations under their rule.

The establishment of the ruler cult under Ptolemy I was not just an extension of Pharaonic tradition, where the office of the king was divine, but the individual was not. Rather, it was a deliberate Hellenistic innovation that deified the living monarch, aligning him with the pantheon itself.

Similarly, Constantine positioned himself not just as a Christian emperor, but as a new kind of ruler, one who mediated between the divine and the temporal. His alliance with Licinius in 313 AD produced what we now call the Edict of Milan, granting legal recognition to Christian worship across the empire. Yet Constantine’s deeper strategy was theological as much as political. By convening the Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, he sought to forge a creedal unity that would serve both as spiritual doctrine and civic glue. Heresy was no longer just doctrinal error – it became a form of sedition against the cosmic order.

Just as Ptolemy I elevated Serapis above local deities to create a universal divine figure for a multicultural empire, Constantine elevated the Jesus character above all other gods. He did not “invent” orthodoxy, but he nationalized it. Through basilicas built at imperial expense, judicial privileges granted to bishops, and tax exemptions codified into law, Constantine wove the Church into the very fabric of imperial governance. The crucified Lord, once a symbol of suffering and humility, was now enthroned on the emperor’s seal, flanked by angels.

Yet both emperors understood that such transformations required careful calibration. Ptolemy’s integration of Egyptian gods like Isis and Anubis into the broader framework of Serapis-worship allowed him to maintain cultural legitimacy without erasing indigenous belief systems (Pfeiffer, 2008). Likewise, Constantine refrained from immediate theocratic dominance. Though urged by some Christian advisors to outlaw animal sacrifice outright, he instead chose selective pressure; closing temples linked to immorality, stripping others of wealth, but allowing pagan shrines to remain so long as public order was preserved (Errington, 1988). He honored his title of Pontifex Maximus, chief priest of traditional Roman religion, while posing as “God’s” chosen friend, a balancing act between majority pagan constituencies and an ascendant Christian (pagan Hellenistic Jews) elite.

The result was a new ontology of power. For Constantine, as for Ptolemy, victory and order no longer came from the capricious gods of old, but from a singular divine source whose will was interpreted through imperial decree. Just as Ptolemaic propaganda portrayed the monarch as a “god-king” embodying both Greek ideals and Egyptian symbolism, Constantine recast himself as the earthly executor of the Jesus character’s cosmic kingship.

This transformation was irreversible. Even later emperors who flirted with reviving paganism found the machinery of the state already speaking the language of the Nicene Creed. As Pfeiffer notes, once a divine figure is enshrined within the imperial apparatus, it becomes nearly impossible to disentangle theology from politics. The god has become king, not only in heaven, but on earth.

Thus, Constantine did not merely adopt a religion, he crowned its Jesus (or its Serapis) as king of an empire. And in doing so, he fulfilled ancient imperial logic: the fusion of professed divine sovereignty and worldly dominion, a vision as old as Ptolemy’s Serapis and as enduring as the pagan cross on the imperial banner.

References

Errington, R. M. (1988). "Constantine as Pontifex Maximus." Greece & Rome , 35(2), 165–180.

Humphries, M. (forthcoming). Constantine and the Conversion of Europe . Oxford University Press.

Odahl, C. M. (2010). Constantine and the Christian Empire . Routledge.

Pfeiffer, S. (2008). The God Serapis, His Cult and the Beginnings of Ruler Worship in Ptolemaic Egypt . Unpublished manuscript.