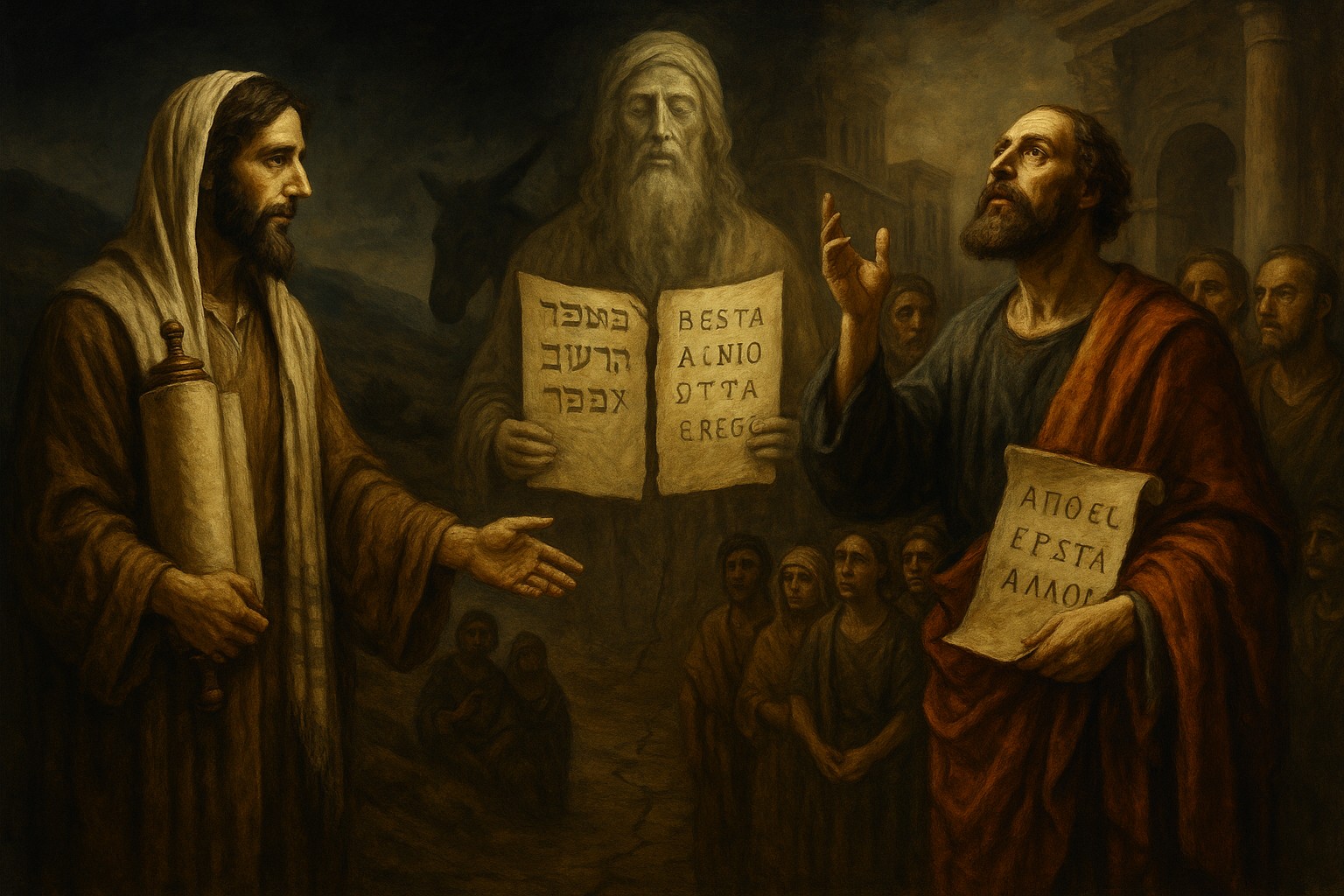

The New Testament paints a vivid picture of the Jesus character, a Hebrew priest proclaiming only the Kingdom of God, and the Paul character, the self-appointed apostle whose mystical encounter with a Christ reshaped early Christianity. But what if Paul’s gospel, often seen as the cornerstone of modern Christianity, diverges from the message of the supposedly historical Jesus? It isn’t difficult to liken Paul to Balaam, the false prophet who blessed what he once cursed, yet remained an outsider, never fully trusted (Numbers 22–24). If Paul echoes Balaam (and he does), what does this say about the gospel he preached? Was it the same as Jesus’ message, or something else entirely?

In this post, I’ll explore the tension between Jesus and Paul in the New Testament, answering whether Christianity today is more Pauline than Jesus-like, and what that means for those seeking an authentic return to the message of that historical Hebrew priest we call “Jesus.”

Paul as Balaam: A Blessing with a Shadow of Doubt

The comparison of Paul to Balaam is interesting. Balaam, a non-Israelite prophet, was hired to curse Israel but was divinely compelled to bless them instead. Similarly, Paul, a zealous Pharisee, initially persecuted the Jesus Movement (Galatians 1:13,14). His dramatic conversion on the road to Damascus (Acts 9) transformed him into a fervent advocate for including Gentiles in the movement he once opposed. Yet, as Wilson (2014) argues, this shift raises questions about Paul’s reliability. Was his gospel a divinely inspired continuation of Jesus’ mission, or did it introduce a new theology that diverged from the original?

Yet much like Balaam, who was compelled to speak blessings over Israel while inwardly remaining suspect and ultimately tragic, Paul enters the Jesus movement not as a disciple of the Nazarene, but as an outsider who rebranded the message for Gentile consumption. Maurice Goguel, writing in Jesus the Nazarene: Myth or History? (1926), observed that “Christianity was born at the beginning of the second century from the meeting of the different currents of thought originating in Judea, Greece and Rome” and that “the person of Jesus was merely a literary fiction” for some early Christian thinkers, highlighting how quickly the focus shifted from the man to the myth (Goguel, 1926, p. 10). Though Goguel himself defends the historical Jesus, his analysis shows that the Jesus remembered by Paul is already a reconstructed figure—one whose teachings were submerged beneath theological reinterpretation.

Similarly, J. Gresham Machen in The Origin of Paul’s Religion (1925) acknowledges the radical divergence between Paul and Jesus. He frames Paul’s theology as something utterly unique, “not merely one manifestation of the progress of oriental religion,” but a wholly different system founded on a particular conception of Jesus’ death and resurrection (Machen, 1925, pp. 8,9). This mirrors the role of Balaam who, though speaking blessings, nonetheless aligned with Moabite interests and introduced elements foreign to Israel’s covenantal ethic. So too does Paul bring into the original Jesus movement an unprecedented fusion of Hellenistic religious forms and theological universalism.

Jesus’ Gospel: A Jewish Vision of the Kingdom

The Jesus character’s message, as depicted in the Gospels (written 20-60 years after Paul’s letters), was deeply rooted in the Jews’ religion (something Paul said he left behind in Galatians 1:13-15). He preached the imminent arrival of God’s Kingdom, urging repentance and a philosophical adherence to the Torah (Mark 1:15; Matthew 5:17). His teachings, like the Sermon on the Mount, emphasized ethical philosophical living, love for neighbor, and obedience to his Deity’s law (Matthew 22:37–40). As Wilson notes, Jesus’ followers, including James, continued these practices, functioning as a Jewish sect alongside Pharisees and Sadducees (Paul versus Jesus, p. 5). Salvation, for this Jesus, was about mindfully living accordingly within God’s covenant with Israel, not a cosmic transaction tied to his death.

Paul, however, rarely references Jesus’ life or teachings. In Paul versus Jesus (p. 19), Wilson points out that Paul mentions only sparse details about Jesus: he was born of a woman, was Jewish, had brothers, was crucified, and died (Romans 1:3; 1 Corinthians 9:5, 15:3). Paul’s focus is on a risen Christ, a cosmic figure whose death and resurrection offer salvation to all, independent of Torah observance (Galatians 3:28). This shift, Wilson argues, moves Christianity from a Jewish reform movement to a Gentile-centric religion resembling Roman mystery cults (p. 15).

Paul’s Gospel: A New Religion?

Pamela Eisenbaum, in Paul Was Not a Christian (2009), challenges the traditional view that Paul rejected Judaism for Christianity. She argues Paul remained a Jew, committed to monotheism, but saw Jesus’ death as God’s provision for Gentiles, not a replacement of the Torah for Jews (p. 9). Paul’s gospel was tailored for Gentiles, emphasizing Jesus’ faithfulness (not faith in Jesus) as the means of their inclusion in God’s plan (Romans 3:22). Eisenbaum suggests Paul’s mission was to extend Jewish monotheism to the nations, not to negate Jesus’ teachings but to reinterpret them for a broader audience (p. 10).

Yet, this reinterpretation created a divide. Wilson highlights that Paul’s letters, like Galatians, show him distancing himself from Jerusalem’s authority, insisting he received his gospel directly from Christ (Galatians 1:11,12). This independence, coupled with his dismissal of Torah practices for Gentiles, led to accusations of distortion. As Wilson (2014) notes, Paul’s opponents in the original Jesus Movement saw his teachings as a departure from Jesus’ Torah-based message (p. 8).

These thoughts are interesting because while Eisenbaum argues that Paul never left Judaism (Eisenbaum, 2009), Goguel’s historical investigation points to a theological re-centering. He writes that “the person of Jesus...is the product, not the creator, of Christianity” for many early communities (Goguel, 1926, p. 11). That statement reinforces the idea that Paul’s letters, with their sparse references to Jesus’ teachings and dense metaphysical framing of the crucifixion and resurrection (see Romans 6:3–11; 1 Corinthians 15), place the Jesus character into a mythic structure alien to the rabbinic ethic found in Matthew or the Didache. Goguel argues that the Gospels themselves are often "dominated by dogmatic and allegorical ideas" (p. 10), suggesting that Pauline theology had already started to shape even the narrative memory of Jesus before it was canonized.

Machen, though defending Paul’s orthodoxy, inadvertently reinforces this divide by admitting that Paul’s gospel required a radical break from Judaism’s national identity: “Gentile freedom, according to Paul, was not something permitted; it was something absolutely required” (Machen, 1925, p. 13). Yet this absolutism is absent from Jesus' teachings, which prioritize righteousness, Torah adherence, and Jewish communal life. The Balaam analogy here becomes sharper: just as Balaam did not curse Israel directly, neither did Paul overtly reject Jesus, but both altered the trajectory under a veil of blessing.

Christianity Today: Pauline or Jesus-Like?

The tension between Jesus and Paul has major implications for modern Christianity. Paul’s letters, written decades before the Gospels, shaped early Christian theology more than Jesus’ teachings. His emphasis on faith over works, universal salvation, and the cosmic Christ became central to Christian doctrine, especially after the Roman Emperors Constantine and Theodosius endorsed Paul’s vision in the 4th century (Paul versus Jesus, p. 3). The Gospels, while preserving Jesus’ Jewish (Hellenistic Jewish) teachings, were later interpreted through an already established Pauline lens, often downplaying their Torah-centric elements.

G.A. Wells, in The Jesus Myth, argues that Paul’s minimal reference to Jesus’ historical life suggests he was more concerned with a mythical Christ than the historical Jesus (p. 19). This aligns with Wilson’s view that Paul’s religion was “quite a different religion altogether” from Jesus’ (Paul versus Jesus, p. 16). Modern Christianity, with its focus on salvation through faith, sacraments, and the divinity of Christ, reflects Paul’s theology more than Jesus’ call for mental and spiritual living within Judaism.

Combining insights from Goguel and Machen clarifies that modern Christianity owes more to Paul’s reinterpretive genius than to the historical Jesus' teachings. Machen notes that Paul’s exclusivist theology; insisting that “there is no other name under heaven...by which we must be saved” (Acts 4:12); drew Gentiles away from syncretic religious expressions and into a dogmatic system (Machen, 1925, p. 9). But that dogma diverged from Jesus’ Torah-centric ethic, one which even Goguel insists was deeply embedded in a specific Jewish framework (Goguel, 1926, pp. 12–13).

In this light, Paul's gospel acts like Balaam’s oracle: impressive, far-reaching, and infused with “divine” imagery, but ultimately carrying within it a “doctrine of Baal” that introduces division. The Jesus character’s original message (should we incline ourselves to actually invoke the Hebrew Scriptures), rooted in covenantal justice, mental spiritual discipline, and community responsibility, becomes eclipsed by a mystical faith in a risen Christ who, as Machen admits, “possessed sovereign power over the forces of nature” (Machen, 1925, p. 5), a cosmic redeemer rather than a Galilean prophet.

What Does This Mean for Seekers of the Historical Jesus?

For those seeking an authentic return to Jesus’ message, the Pauline influence poses a challenge. Jesus’ gospel was not about himself at the center of a message, but about transforming human lives through ethical conduct and Torah observance, anticipating only God’s Kingdom within and the Son of Man (who he is not) destroying those preventing the reign of that Kingdom within doers. Paul’s gospel, while rooted in Jewish monotheism, shifted the focus to a spiritual salvation through his Christ’s death, appealing to a Gentile audience. As Eisenbaum notes, Paul didn’t abandon Judaism but adapted it for a new context (Paul Was Not a Christian, p. 10). However, this adaptation, as Wilson argues, created a rift with the Jesus Movement, leading to a Christianity that often overshadows Jesus’ original vision.

If Paul is a literary echo of Balaam, his gospel carries both a blessing and a shadow. He blessed the inclusion of Gentiles, expanding the reach of his God’s message, but his divergence from Jesus’ teachings left him distrusted by the Jerusalem community. For modern seekers, returning to the original message of Jesus means prioritizing his call to discipline the mind, to educate the belief, to remember love, justice, and covenantal living with the Hebrew Deity over Paul’s theological framework. This involves separating Hellenism from the Jesus character to embracing the covered up Hebrew philosophy within his teachings, which align more closely with the original Jesus Movement (Paul versus Jesus, p. 27).

Reclaiming the Historical Jesus

The question of whether Christianity is more Pauline than Jesus-like invites us to reexamine the New Testament’s competing voices. Paul’s gospel, while transformative, reshaped Jesus’ possibly original message into a universal religion that gained traction in the Roman world but drifted from its Hebrew roots. Paul, like Balaam, spoke words that appeared to honor the people of God, but his doctrine redirected their path. It isn’t difficult to see how Paul's gospel, though influential and theologically sophisticated, transformed the original Jesus movement into a religion barely recognizable to its origin. For modern seekers of the historical Jesus, disentangling his message from Pauline overlay is not only a matter of academic curiosity, it is a necessary task of devotional restoration. Christianity may be Pauline in shape, but our devotional conversation need not rest on what ultimately departs from the intended growth and development promised from Genesis to Malachi.

References:

Eisenbaum, Pamela. (2009) Paul Was Not a Christian. HarperCollins.

Goguel, M. (1926). Jesus the Nazarene: Myth or History? (F. Stephens, Trans.). D. Appleton & Company.

Machen, J. G. (1925). The Origin of Paul’s Religion. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

Wells, G.A. (1999) The Jesus Myth. Open Court.

Wilson, Barrie. (2014) Paul versus Jesus. York University, Toronto